This article was originally published on dazeddigital.com

We explore the photographers who took influence from mortality, eroticism and existentialism.

When photography was discovered in the early 1800s, audiences were enraptured. Fascinated by the idea that time could be frozen, the medium was approached with the utmost rationality. But what early consumers could never have anticipated was its potential for turning reality on its head – achieved by photographers delving into the human psyche through their lens. From the 1920s, visionaries began unlocking the fantastical potential of the camera by experimenting and introducing new techniques that enabled them to actualise the darkest parts of the human mind.

Often through black and white film, photographers explored the human psyche by referencing the psychoanalytic theories of the likes of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, interrogating topics we often struggle to talk about, such as the uncanny, absurd, sublime, and macabre, alongside morality, religion, eroticism, and existentialism. Underlining most of these psychological explorations was the notion of social taboo, which this style of photography so powerfully destructs.

In celebration of the avant-garde photographers who revolutionised the medium to create some of the most complex photography to ever exist, here are six names you must know.

“(My) pictures in some way ring a bell subconsciously, so people remember them” – Roger Ballen

EIKOH HOSOE: JAPANESE PSYCHO-THRILLERS

Photographer and filmmaker Eikoh Hosoe’s imagery dives into the darkest corners of our minds. Drawing on an eye for film, Eikoh creates other worlds which are shaped with skillfully crafted, unnatural scenes and horror-esque landscapes. His most esteemed photo series, Kamaitachi (1969), recreates the fable of a demon who haunts rice fields in rural Japan and slashes people with a sickle. A surrealist, Eikoh emerged off the back of post World War II realism and added a new texture to Japanese photography by weaving gothic references and dark and gritty contrasts that explore death, eroticism, religion, and irrationality.

“The camera is generally assumed to be unable to depict that which is not visible to the eye and yet, the photographer who wields it well can depict what lies unseen in his memory,” Eikoh once stated in a press release. On top of his work, the photographer was the leader of many avant-garde artist groups, including The Jazz Film Laboratory which he started in the 1960s after being a student at the Tokyo College of photography with fellow photographer Shōmei Tōmatsu. It is said that Eikoh revived Japanese sensibility at a time of cultural upheaval, allowing Japanese society to understand the dark underlinings of its psyche at a time of great cultural change.

DORA MAAR: THE SURREALIST INTERIOR MODE

One of surrealist photographer and impressionist painter Dora Maar’s most circulated images is a portrait of Pablo Picasso working on his infamous Guernica paintings in 1937. On top of this, Maar is widely known as the muse for Picasso’s “Weeping Woman” (1937). The canonisation of Maar through the lens of her nine-year relationship with Picasso comes as no surprise considering the deeply embedded sexism of the art world. But what classic representations of Maar glaze over is an entire body of deeply psychological, surrealist photography that heralded the surrealist idea of the interior world. Her photography shows the way that surrealist symbolism explores the inner workings and emotions of the human mind.

Starting her photo career as first assistant to Man Ray, Maar worked predominantly in black and white and drew on surrealist symbolism like shells, shadows, and hair always rendered in haunting tones. While these are symbols known to the common eye, Maar uses them in unconventional ways to create dream-like landscapes that explore her mind. In “Rue D’Astorg” (1936), Maar takes a passageway and distorts it into a dizzying spell as if to hypnotise viewers, as her subject (a mummified sculpture) stands creepily before it. This image is reflective of the way Maar harnessed photography in a way that used psychological techniques to extend photography beyond realism.

JOEL PETER WITKIN: THE PSYCHOLOGY OF TABOOS

There’s something intangible about topics which society considers taboo: death, eroticism, and religion are all intoxicated with the same kind of spirituality that makes them hard to grasp. American photographer Joel Peter Witkin is a master of actualising this spirituality: his photography turns what most of us find even hard to speak about into hauntingly dark imagery.

Witkin’s fascination with morality began after he was severely shocked from witnessing a car crash and subsequent death at the age of six. This permanent shock travels as waves across Witkin’s 50-year career of creating images which he intends to be as powerful as the last image a person sees or remembers before death. Witkin’s 1983 image “Sanitarium” deals with mortality and the life cycle between animals and humans so powerfully that it inspired designer Alexander McQueen’s entire SS01 VOSS show. The grey scale, heavily shadowed image features a woman wearing an inverted gas mask whose tubes she shares with a monkey that hangs from the wall. “There is for me in this situation a strange, terrible sense of being forced to view the events in rooms of asylums or places of torture,” explains Witkin. “But most importantly, it is a depiction of an egoless being, a shaman in existence here and beyond.” Everything about “Sanitarium” is claustrophobic as the image’s breathlessness alludes powerfully to the ever impending weight of death.

CLAUDE CAHUN: THE HUMAN CONDITION ON GENDER AND IDENTITY

French artist Claude Cahun spent her entire life exploring the duality of her gender identity through art. Born Lucy Renee Mathilde Schwob, at the age of 23 the artist legally changed her name to the gender-ambiguous Claude Cahun as she began to make work that challenged the stagnancy of gender roles in the early 1900s. Predating the transformative performance work of Cindy Sherman, in her self-portraits Cahun assumed different gender roles to explore how the psychology of being a man or a woman transcended into these personas, from dandy to doll, vamp and vampire, bodybuilder and angel. Cahun described the exploration of her psyche as a “hunt”, as she relentlessly explored the different gendered elements of the self.

In Cahun’s 1928 photo “Que Me Veux-Tu”, the psychological theory of the uncanny and the double comes to life. Ideals of the double pose that our ego is made in two parts and that our subconscious, uncanny double follows us in the forms of shadows, reflections, and mirrors (symbolism which features widely across Cahun’s work). In “Que Me”, Cahun appears as a two-headed androgynous creature which stands as a metaphor for the division of her identity. What’s critical of Cahun’s exploration of the double (impressive photo techniques aside) is how she uses the camera as a tool to manifest this identity – without the medium of photography, this double identity exists only within the mind. “Divide myself in order to conquer, multiply myself in order to assert myself,” Cahun once wrote of her work. The divided self echoes throughout Cahun’s entire body of work, using mirrors and photographic effects to continuously reproduce her other self.

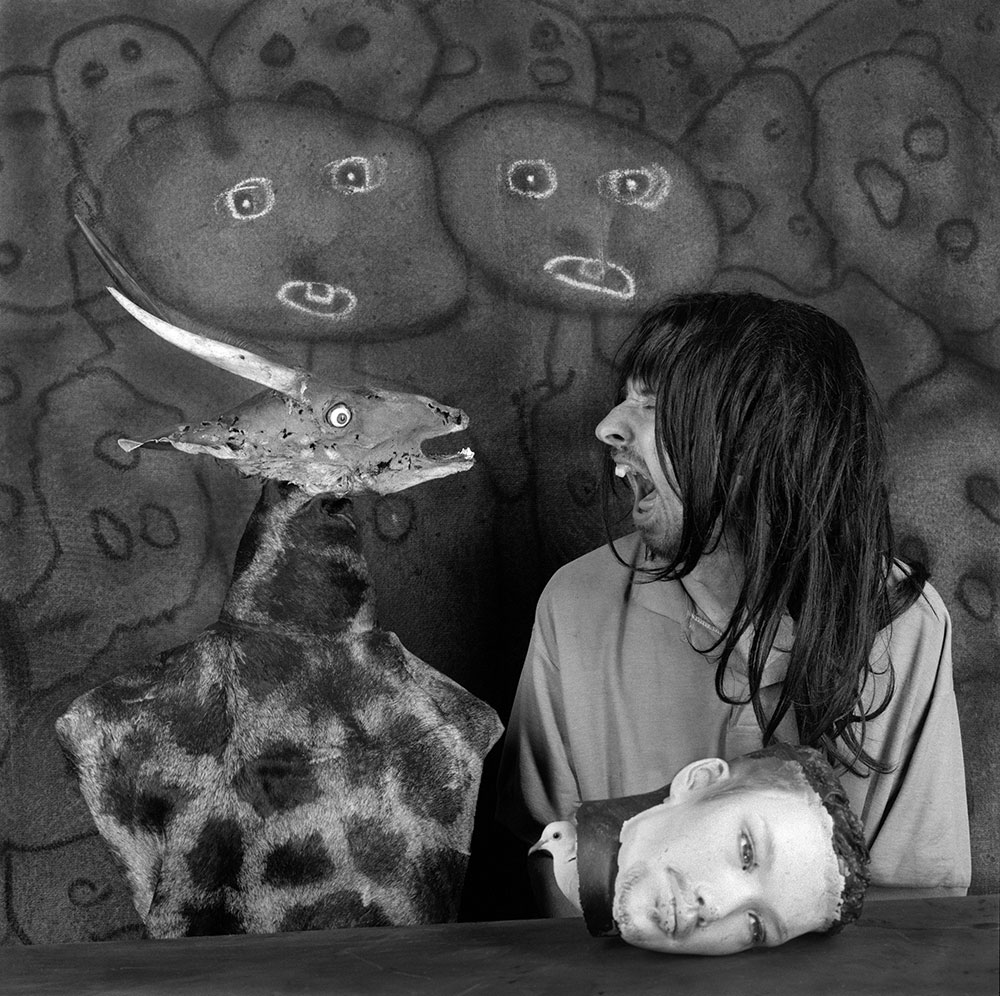

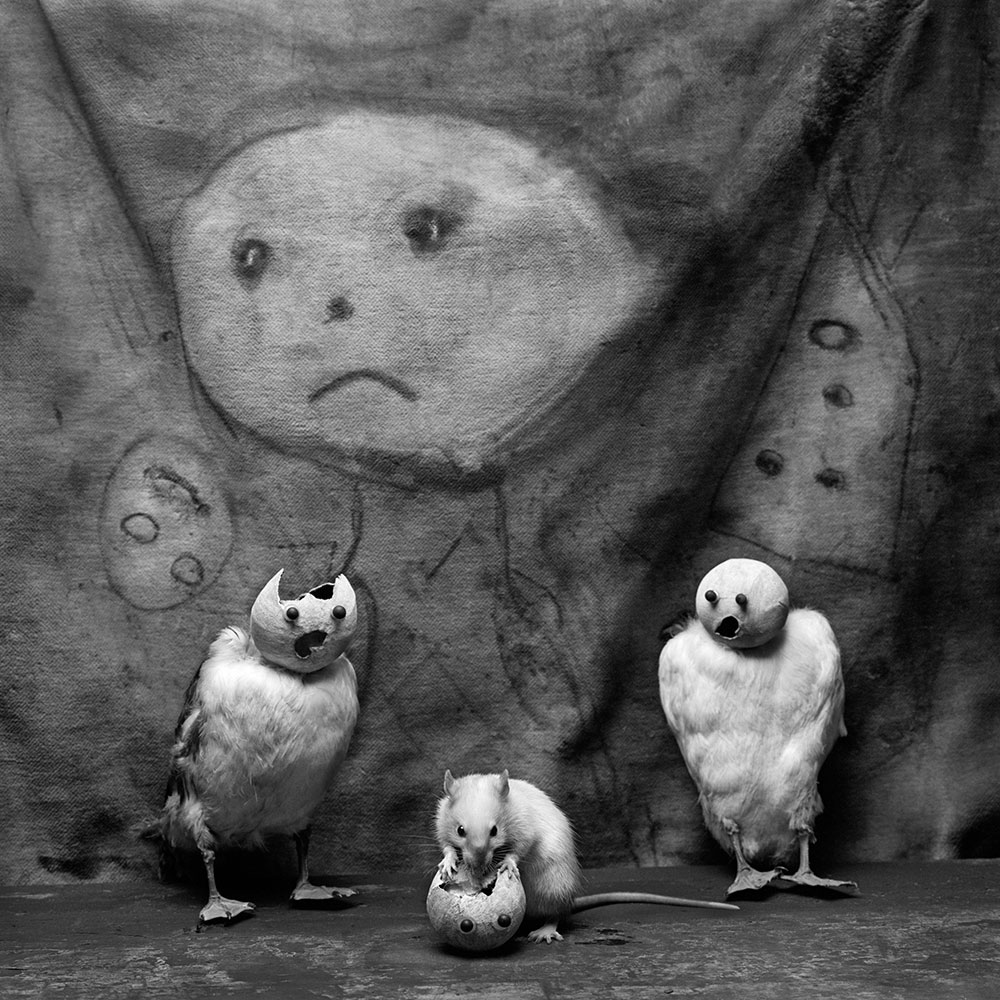

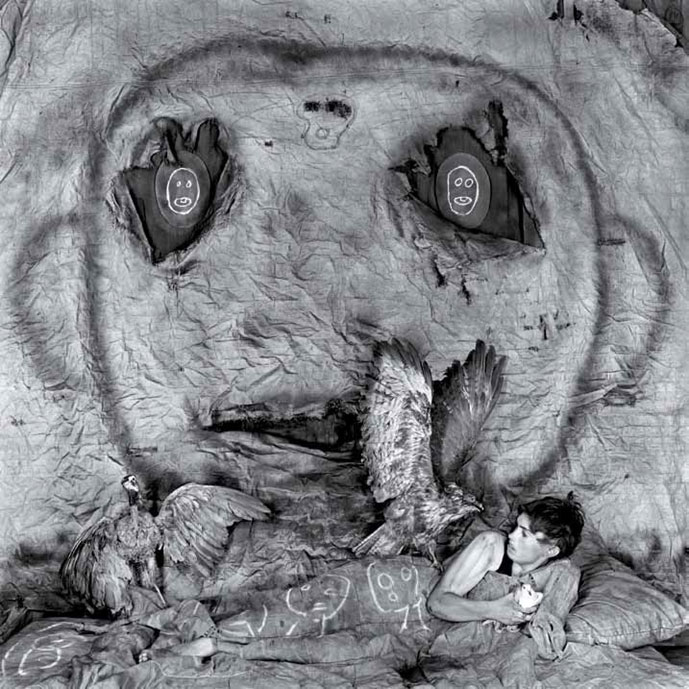

ROGER BALLEN: EXISTENTIALISM THROUGH ABSURDISM

Few photographers ditch the realism of the craft so powerfully like South African artist Roger Ballen, who swaps photographic clarity for pure absurdism. Ballen’s photos exist in a parallel world: they are frantic, deeply psychological explorations of existential ideas like life and death, human relationship to the animal world, and life in space. Child-like etchings sprawl his walls, human limbs appear out of nowhere, animals and humans converse in absurdist ways. “Absurdity has a very deep, existential relationship to people’s understandings of themselves even though they may not admit it,” Ballen once reflected on his work for Dazed. “We all know that we are here for a limited amount of time, we all know that we really don’t know why we are here, we all know that ultimately, no matter, we are going to die. We all know these things even though we don’t want to admit to it. Or we try to run away from it. But those pictures in some way ring a bell subconsciously, so people remember them. And whether they want to admit to it or come to terms with the meaning, it’s there. It’s right in your face.”

Ballen takes inspiration from the psychoanalytic writings of Sigmund Freud (the pair sharing the same knack for existentialism). “In the art side, the greatest influence for me is art brut: artists who explore primitive art, children’s art, insane art,” Ballen explains. The influence of Freud and art brut seeps through works like his series Shadow Chamber (2004-05) which uses absurdism and dark themes to explore the underbelly of humanity. “For me, darkness is a challenge – it’s about the unknown. If you say part of my mind is dark, then it is something unknown and something I want to charter and find out more about. It’s hidden from me and I think there’s a lot of truth hidden.”

FRANCESCA WOODMAN: PSYCHOLOGICAL ERASURE

On January 19 1981, photographer and artist Francesca Woodman committed suicide at the tender age of 22. Her work was a poetic assertion of the female gaze whose artistic techniques and black and white contrasts are seen as attempts of psychological erasure. Woodman’s existential works tamper with the idea of being alive.

Addressing Woodman’s work through the lens of mortality is something photographic theorist Peggy Phelan feels critical to understanding Woodman as an artist, and the power of art to explore the suffering psyche. “People close to those who have committed suicide often worry that they might have missed a clue, a cry for help, a retrospectively enigmatic message; they often replay conversations to see if they could have done something to prevent the suicide,” reflects Phelan. “The art critic similarly returns to the same images, scrutinising them to see what they might portend about the psychic condition of the artist. This is tricky because it threatens to turn art into nothing more than psychological symptom… I want neither to romanticise death nor to contribute to an essentializing view of ‘the suicided artist.’ Not all of Woodman’s work concerns death, but I believe her preoccupation with it permeates her understanding of photography. Indeed, it is my contention that her interest in death allows us to glimpse an unusual view of what death and art, together and separately, might mean.”

Phelan argues that Woodman’s exploration of death resides in her unique use of techniques, focusing on her tendency to blur her self-image to elicit ghostly like self-portraits where Woodman almost vanishes. Take “Untitled“ Boulder, Colorado, 1972–75 which sees Woodman’s body in long exposure appear as a ghost travelling through a gravestone. “I’d like to think that Woodman was able to use her photography as a way to explore the enigma of her relationship with her own developing and vanishing image… Woodman found in her art a type of theatre for the oscillating tension between the desire to live and the desire to die.”

Comments are closed.