This article was originally published on japantimes.co.jp

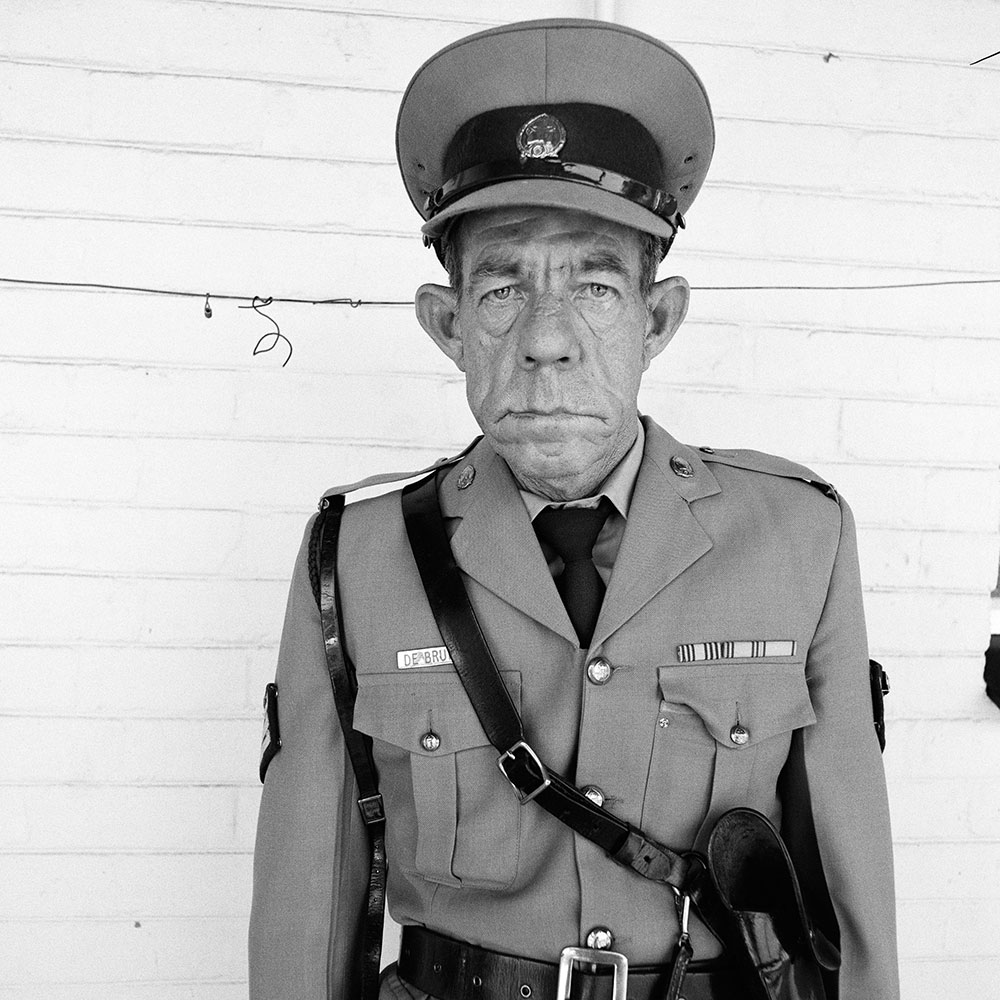

In one of Roger Ballen’s most well-known images, a picture of F. de Bruin of the Orange Free State prison service, the elderly sergeant looks out at us with the forlorn look of a tired beagle, not at all the face of an enforcer of white supremacy. The subject’s belt is slack, his uniform slightly too big for his small frame, with the stitching coming apart on the lapel.

Ballen composed the shot so that a wire traversing the frame behind the sergeant’s head exactly coincides with the subject’s eye level and subtly cuts the image one third of the way down. Ballen has commented that it was in fact a twist in the wire that had originally piqued his interest, and that the prison officer turned up after Ballen had decided to take a closer look at this small detail.

The image is square, like all of Ballen’s work, and it’s no coincidence that the two photographers that Ballen is most compared to, Diane Arbus and Joel-Peter Witkin, are also known for using the square format. The neat geometry of the square strongly encloses its subject matter, shutting it off from the outside world. At the same time as being more self-contained than the rectangular format, the square has a formality and stability to it, which, on the face of it, seems to run counter to the aberrant, horror-inflected nature of the content pursued by Ballen and his aesthetic compeers.

The very beautifully organized and presented exhibition “Ballenesque” at the Emon Photo Gallery includes Ballen’s early photo-documentary work through to his most recent series, “The Theatre of Apparitions,” whose images of semi-human creatures and staring eyeholes, reminiscent of Paleolithic art, are created by photographing spray-painted glass that has been scraped and scratched to allow light through. The venue itself, an impeccable space in Tokyo’s swish Hiroo neighborhood, has undergone some tweaking in order to turn it into a more “Ballenesque” immersive experience. Faces and figures have been drawn, in art-brut style, on the bare concrete surfaces of the gallery and there is a pair of creepy child-size mannequins set up at the entrance.

Looking a little like yōkai — the Japanese folkloric demons that vary between scary and comic — the childlike sketches that have featured in Ballen’s work since he began deliberately constructing images, are now taking precedence over the grimy rooms, animals and distressed bodies with which they appeared in previous series. These drawings now lend themselves to being read as more playful and tongue-in-cheek. Ballen himself has commented on different occasions that readings of his work as “dark” are really only a projection of some viewers’ inability to face their own darkness — what Carl Jung called the “personal shadow.”

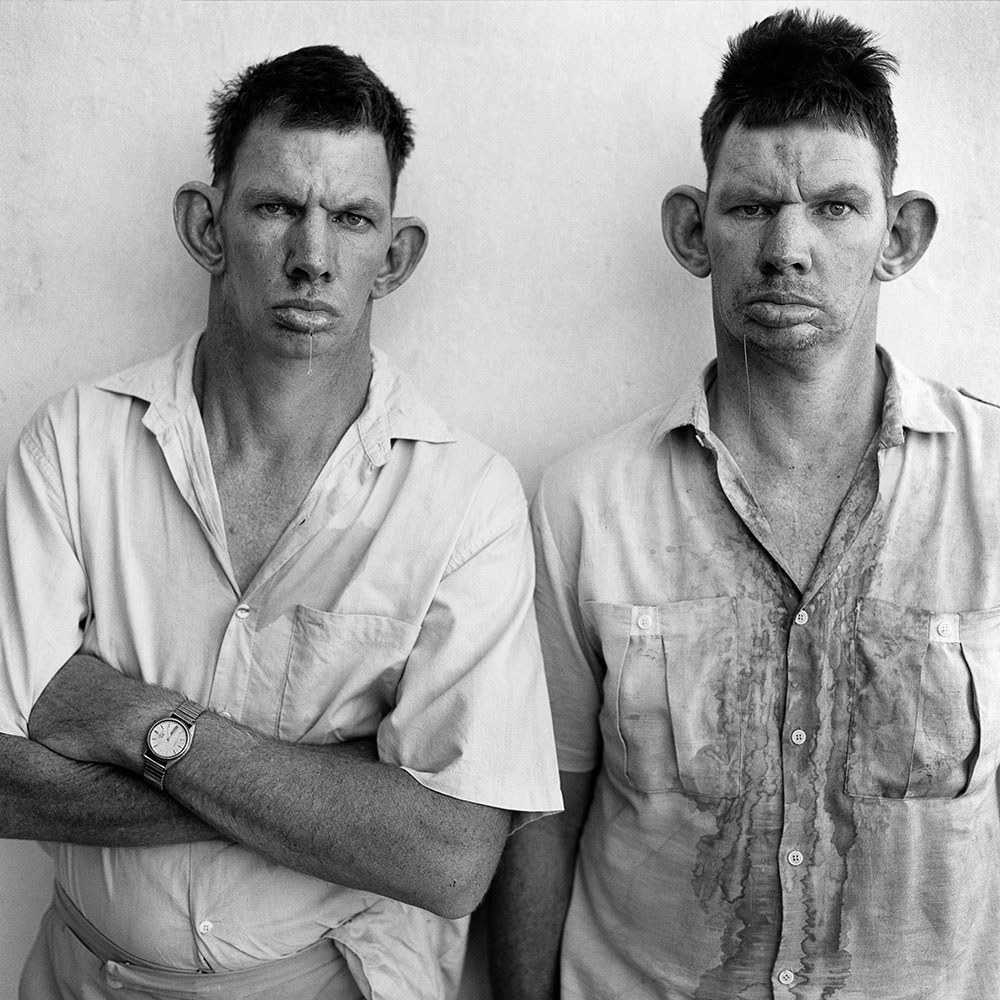

Ballen has also been keen to point out that his primary interest is his own psychological journey, not politics or social issues, despite the setting of his work being decrepit economically deprived environments loaded with socio-political import. The context that Ballen has said that his work should be taken in is the exploration of the “human condition” in general.

It could be said that Ballen is unusually prescriptive about how his work should be viewed; perhaps this is a consequence of having taken some flak for photographing the vulnerable for the pursuit of his own ends. As a matter of creative process, though, it should not be surprising that an artist who pays the highest attention to composition should also be concerned about framing how his work is seen.

“Ballenesque: Roger Ballen Exhibition” at Emon Photo Gallery runs until Dec. 20; 11 a.m.-7 p.m. (Sat. until 6 p.m.). Closed Sun. and holidays.

Comments are closed.