This article was originally published on sz-mag.com

“My images are meant to straddle a strange line, where illusion becomes delusion, fact is fiction, and the conscious merges with the unconscious. Dreams become real, the real becomes a dream, the dead is alive, the alive dead,” says the photographer Roger Ballen, who lives in works in South Africa, in a video accompanying his new book, Ballenesque.

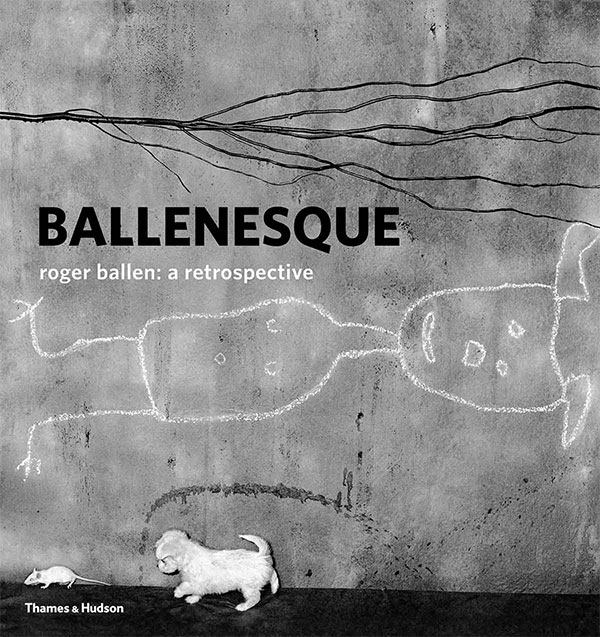

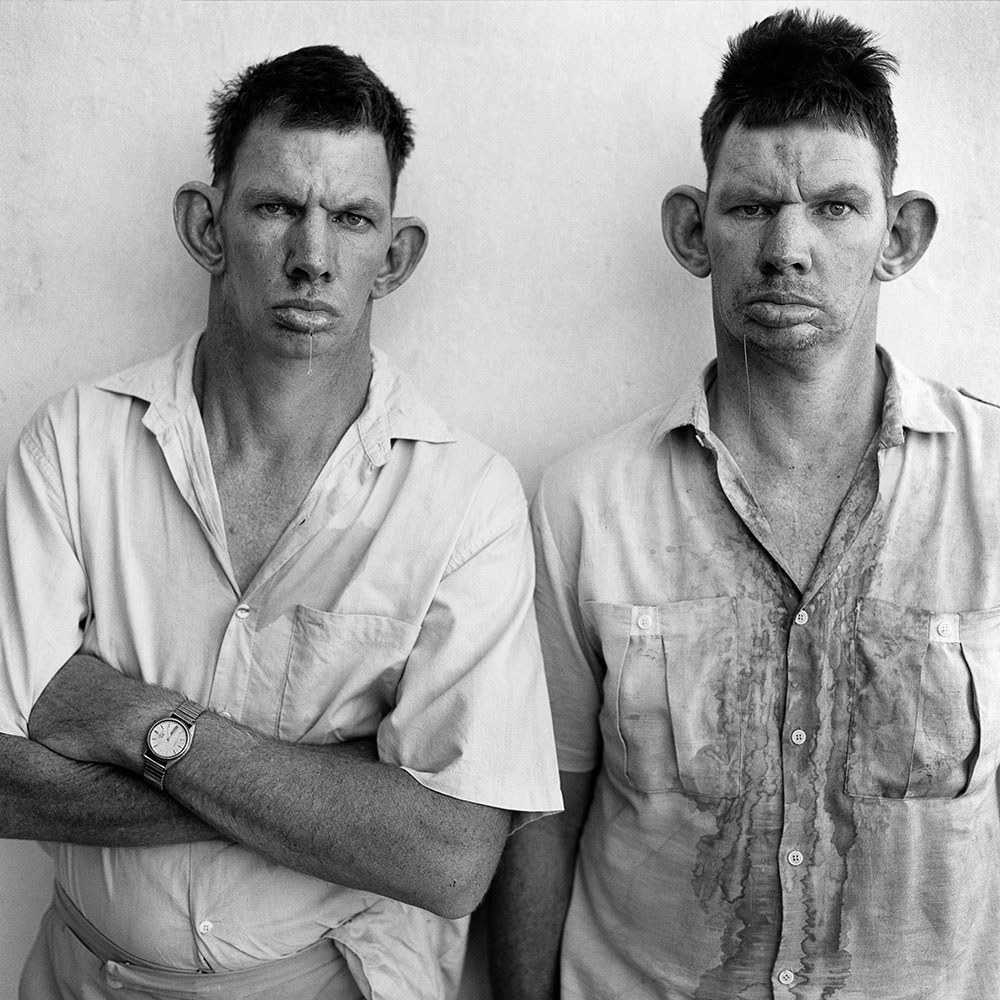

The 366-page monograph, contains 345 illustrations, mostly photographs and some paintings, and is the first comprehensive retrospective of Ballen’s work. Ballen, became famous for photographing the dregs of humanity, the decrepit, the crazy, the filthy outsiders that the society would rather pretend do not exist. But they do exist, the inhuman humans, men morphed back into something lower. Ballen, who is a geologist by education, moved from his native New York state to Johannesburg to work in its minding industry, but he’s always had a camera with him, a debt he probably owed to his mother, who was a member of the Magnum photo agency in the ‘60s, and who passed away prematurely in 1973.

Ballen’s first work of note was Drops: Small Towns of South Africa, but he did not achieve notoriety until his 2001 book, Outland. The book cemented his reputation as the photographer of the willfully forgotten underclass. In 2012 the South African rap duo Die Antwoord asked Ballen to produce a video for its first single “I Fink U Freeky,” which became an enormous hit and propelled Ballen into popular culture.

To look at Ballen’s images requires certain strength, an ability to squarely look at human grotesqueness on the most intimate scale. There is no didactic admonishing in them about the plight of the underclass; they are not meant to send us on another pointless guilt trip while scoring the photographer cheap humanitarian points. What you get instead is a feeling of sympathy coupled with existential dread.

As Ballen progressed in his career his images became increasingly surreal. He worked a lot on settings, using drawings, animals, and masks as props. If there is a precursor to Ballen’s late work, it’s that other master of the grotesque, Joel-Peter Witkin. But whereas you could quite easily disassociate Witkin’s images from reality (though they were very real in actuality), Ballen, like Kafka, pulls the surreal squarely into the mundane. The subhuman surroundings in which his subjects live, the dirt and the grime are very much real, almost a matter-of-fact real. What is repulsive to us is normal to them. What civilization has worked so hard to get away from is very much present. Ballen’s work is the end of the line.

On some level it’s hard to believe that a retrospective monograph on Ballen is out only now, when he is 67. But it arrives with self-confidence – to add “-esque” to one’s own work is a ballsy move, since it’s usually reserved for a cultural figure who has been able to conjure up a complete world, whether aesthetic or that of ideas, and is, well, dead by the time his impact is made. The term becomes a shortcut for something complex and nuanced, and is usually reserved for authors. When we talk of Kafkaesque (or Orwellian, or Wildean), we know what we mean. As a matter of fact, there is something Kafkaesque in Ballen’s work, and I would love to see a publisher produce a volume of say, Metamorphosis, illustrated by Ballen.

And yet, I think Ballen deserves his own “-esque,” not only because his work is stylistically unmistakable, but exactly because he has been able to conjure up a world. In this world, and I could not have said it better than the artist himself, “Chaos prevails over order, it dominates the human condition, there is no direction, no ultimate purpose, confusion and loneliness reign… My favorite word in the English language is ‘nothing.’”

Comments are closed.