This article was originally published on australianbookreview.com.au

Roger Ballen’s art is not for the faint-hearted; it is confronting, haunting, and at times repellent. It is also fascinating, brilliant, and jaw-dropping. These images seethe with malodorous discontent, menace, and psychosis. The best way to experience his photographs is to surrender and resist the desire to read the images literally, for it is in the hidden recesses of the imagination that Ballen’s images come to life.

Born in 1950, Ballen was exposed to photography at a young age, growing up in what could be considered the inner circle of New York’s photography scene: his mother opened one of the first photographic art galleries in the United States in the 1960s with Magnum Photos’ André Kertészand Henri Cartier-Bresson. Ballen came to photography after experimenting with drawing and painting, but it wasn’t until he was in his fifties that he left behind a career as a geologist to reconnect with his artistic soul.

For more than thirty years, Ballen has lived in South Africa. It is the encounters he had with those living on the margins of society, first in Hopetown and later Johannesburg, where he resides, that had a profound impact on his photographic practice. Instead of photographing what he could see on the outside, Ballen turned his gaze inside and inward, literally and metaphorically.

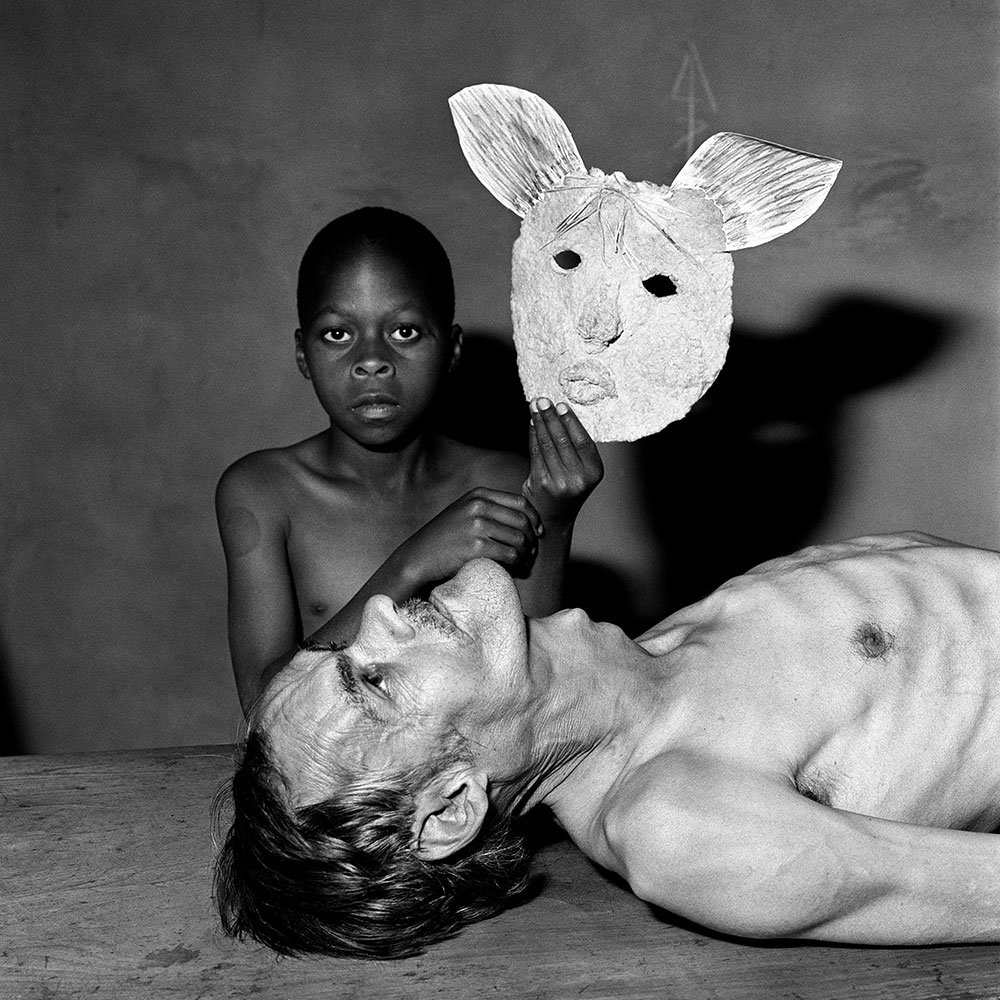

Ballen’s pictures draw focus on those ostracised by poverty and mental illness, and express ideas about alienation from our inherent connection with nature to challenge the values of contemporary society. The visual tropes of untamed spaces, shadow worlds, and wild animals found in Ballen’s photographs are redolent of the primitive relationships that humans once had to their environment. These edgy, confronting works are founded on the concept that ‘the animal is deep inside … we come from the animal’, explains Ballen. This is an idea he says that Western society has largely subjugated, and his images are designed to contest what he describes as modernity’s antiseptic existence.

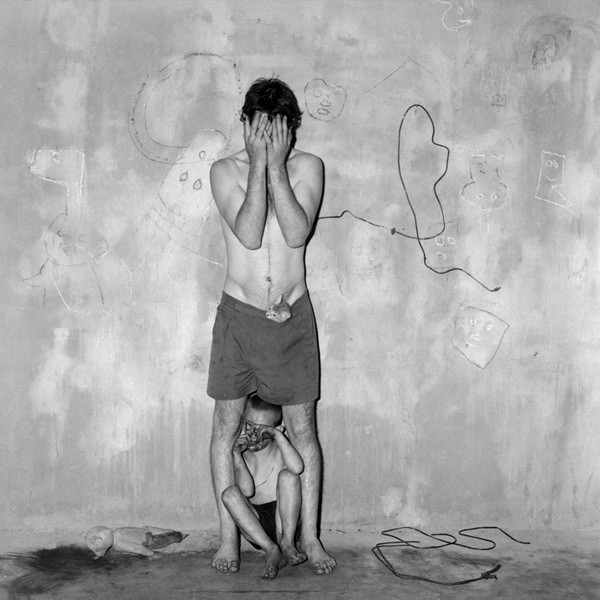

Today, Ballen is considered one of the most revolutionary and important image-makers. A defining feature of Ballen’s aesthetic – which is known as Ballenesque – is the use of drawings, paintings, and sculptures in photographs, some of which are made by the artist himself, and others by those pictured. To enter Ballen’s ‘shadow world’ (he doesn’t like the negative connotations of the word ‘dark’) is to accept an assault on the senses. This work, with its palpating energy, chaos, and confusion, depicts bizarre scenes where human beings and animals interact in scenarios that are both absurd and frightening, where sanity and madness collide, where anything can, and does, happen.

While these pictures feature real people in situ, that is where the documentary aspect of Ballen’s work ends. This is a theatrical interpretation of reality, a fusing of fact and fiction. Crafted in collaboration with the subjects under the direction of Ballen, his intention is to create work that ‘straddle[s] the strange vague line where illusion becomes delusion, fact is fiction and the conscious merges with the unconscious’.

Ballenesque is also the name of the retrospective currently on show at GAGPROJECTS (formerly Greenaway Art Gallery) as part of the Adelaide Festival. The exhibition features twenty-three images from his widely lauded bodies of work Outland, Shadow Chamber, I Fink U Freeky, Asylum of the Birds, and Boarding House, as well as rarely seen pieces.

There are also several of Ballen’s short films on a loop – No Exit (2018), Ballenesque (2017), Outland (2015), Asylum of the Birds (2014), and I Fink U Freeky (2012). In a dark, curtained-off room, guests on opening night sat or stood in silence transfixed by the black-and-white films that bring many of the images on the walls to life. Seeing these people animated adds to the unnerving nature of Ballen’s work. The films also show how Ballen interacts with his subjects, the collaborative associations he forms, and the trust these outsiders have in this man who lives in a world as far removed from their reality as theirs is from his.

Using photography as a frame, Ballen transforms the space depicted through a union of artistic elucidation, theatrical rendering, and visual documentation in black and white, in shades of gray. As you open your mind to Ballen’s bizarre and at times grotesque realm, you discover that these compositions, which at first may confuse, amuse, or frighten, are meditations on the human condition. Maybe that is why the reaction to his pictures can feel so visceral: what we are seeing is at once foreign and yet strangely, perhaps subconsciously, familiar.

Many of the settings in which he shoots are defined by decaying architecture, windowless rooms, and walls covered in graffiti creating dramatic backdrops for his sets. Animals often appear in his images and in his short films: ‘dead or alive, wild or tame … in places they don’t belong’. Humans interact with these creatures in crazed, chaotic scenarios. In the film I Fink U Freeky(2012), rats crawl over a young woman’s semi-clad torso and between her legs; in Asylum of the Birds (2014), chickens lose their heads, while others are cuddled as pets. In this turmoil is a compelling proposition that asks the viewer to confront what it is they are most frightened of seeing.

Ballen says he thrives in environments ‘characterized by chaos and confusion’, but he is also aware of the dangers that come with working on the margins in spaces where humans are ‘fragmented’, animals roam free, and lucidity is often absent. He also reveals that on occasion he has postponed shooting, the atmosphere so fraught as to be physically threatening.

The multiple ways in which one can respond to the work is what makes Ballen’s approach so interesting. Each image is an enigma. The trick is to try and not solve the conundrum he presents but to embrace its boundary-less form and engage instinctively, not intellectually. It seems pointless to expect resolutions to the existential questions his photographs pose when Ballen admits his pictures have ‘no answers’.

Ballen’s body of work has evolved over a long period of time and has involved ‘a lot of hard work, struggle, concentration, a lot of time and money, and a lot of passion’, he says. ‘All these things have contributed to what I do. I don’t do work for other people, I don’t think about other people. I hope other people are affected in a positive way, but I’m not trying to out guess the market, or figure out what will sell, what will do this or that. I just do it for myself … I am not creating art for commercial purposes. I think the day I do that I will quit.’

Ballenesque does what art is meant to: outrage, challenge, and provoke. Ballen’s images and films resonate at a deep emotional and psychological level. Knowing that this shadow world is real yet hidden from most of us is disconcerting. In illuminating its existence, shadows are cast across our bright, urban lives making us question our own values. Ballen suggests that ‘the light comes from the dark’ and that by engaging with these confronting images we may learn something about our own humanity. It’s an interesting proposition.

Ballenesque, Roger Ballen: A Retrospective is currently showing at GAGPROJECTS as part of the Adelaide Festival from 27 February to 31 March 2019.

Comments are closed.